Sir Francis Bacon said “Knowledge is Power” and to be in possession of Power is fulfilling. The book “Superpower Syndrome” does not deal with the absolute nature of knowledge but reaches for a step further in analyzing the effects (or side-effects, if you may) of a “Superpower”. The belief, which you attain, of being in control of everything and thus dressing up in an invisible attire of “Superpower”. The author is unguarded in his dealing with America’s Superpower status and coins the term “Superpower syndrome”, the core of which is vulnerability. The author, Robert Jay Lifton, is a visiting professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and has been conducting psychological research on the problem of apocalyptic violence. His research on the psychology of genocide and healing through killing is well known. Lifton’s views are shared in this post for better understanding of the vulnerabilities that a superpower withholds.

Manifestation of Super Power Syndrome

Lifton, after the completion of the book, reflects on the sad and dangerous times ahead. America had just ended the first phase of its war with Iraq. As an American, Lifton (much like his fellow Americans), is confronted with two starkly contending narratives about the war. The first, put forward by the war planners, that the war is to liberate the Iraqi people from the cruel dictator, the disarming of a dangerous regime (even if its weapons of mass destruction were to be found) and to enable democracy to take root in the Middle East. The second narrative is of the American superpower seeking to dominate the Middle East and the world at large, and now actively threatening other countries (Syria, Iran, and North Korea) with similar fate, if they did not adhere to America’s dictum.

America has fought a “pre-emptive war”, one fought in response to an attack the enemy has initiated or is in the process of initiating. The author, infact, embarks that it was a preventive war, which the American leaders deemed fit to engage, in case Iraq becomes dangerous to their land in the future. The author continues to state that the “danger” that was “prevented” was the impediment posed by Iraq to the American domination of the Middle East and the world itself. In other words, the American leaders cherished a dream, which was extreme and apocalyptic. The invasion of Iraq was followed by the fanatical Islamist violence of September 11, 2001 and the American response that took the form of an amorphous “war on terror”. That “war” is a manifestation of what the author calls the “Superpower Syndrome”. It’s a medical metaphor meant to suggest aberrant behaviour that is not just random but part of a more general psychological and political constellation. That constellation – the syndrome – developed in the aftermath of the World War II but has recently taken a world-endangering form, the author suggests.

Apocalyptic Violence and Human Nature

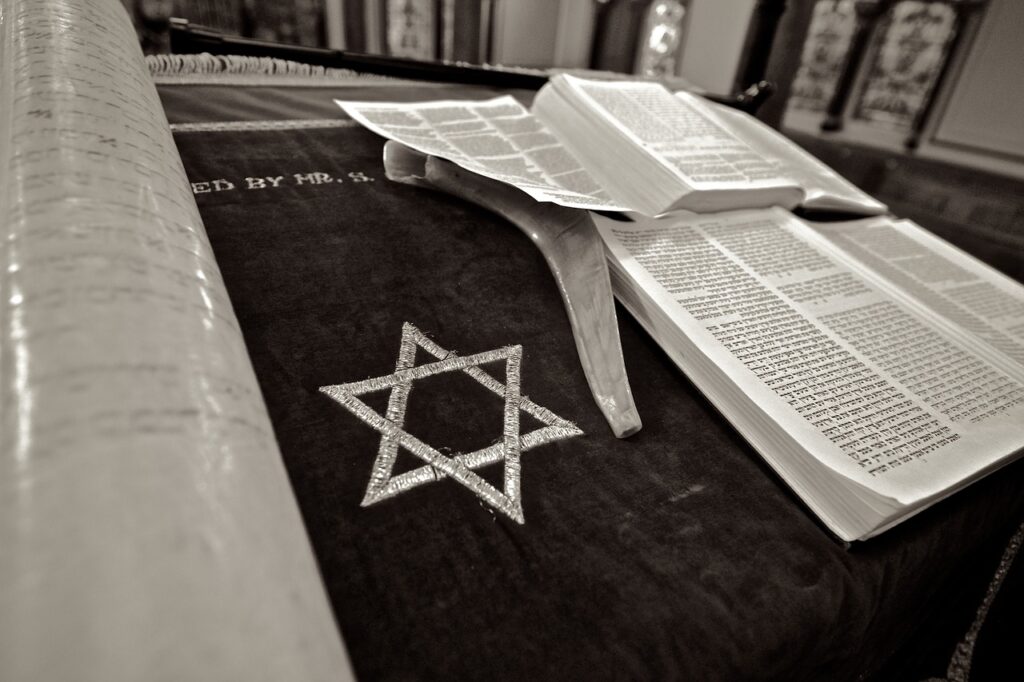

It is appropriate to think of apocalyptic violence as a form of ultimate idealism, a quest for spiritual utopia. The word apocalypse derives from the Greek term for “revelation” or “uncovering”. In Judaism and Christianity, the apocalypse came from God and concerned a powerful event. In Christianity, the apocalypse involves visions of untold vistas of destruction, only foretold a new beginning. The all-consuming violence is required for lofty rebirth to follow.

“Physical death is not an ultimate disaster” as religious scholar John Collins puts it. There is a life, and there are values which go beyond, or transcend, death. The purpose of the apocalyptic is to foster the cherishing of values which transcend death and thereby the experience of transcendent life. That sense of transcendent cosmic order can be internalized and the individual believer is suddenly made to feel his life newly purposeful and in touch with eternity. More than a sense of immortality, he feels himself in alliance with his deity.

The author queries, what could be more grandiose that a vast plan to save the world by destroying it while exercising ownership over death itself? But for the participants, it is not them but God (or the equivalent) who is being grandiose, and He has complete claim to be just that. Leaders and instigators of apocalyptic projects, in their claimed alliance with God (or history), become grandiose and sometimes megalomanic in subsuming the world itself in the name of God, even replacing the world with self.

Looking at the World War I and the Armenian genocide, World War II and the Holocaust, Soviet and Chinese Communism, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Vietnam war, genocides in Cambodia and Rwanda and the near genocidal acts and wars in the former Yugoslavia, it can be said with certainty that the last century was an arena of contending visions of purification, one seemingly more murderous than the next.

Vietnam and Superpower Psyche

Vietnam has a special importance for the superpower syndrome, as it was the first significant defeat of a superpower in the recent times. The Vietnam War demonstrated that a relatively small and technologically limited country, on its own terrain, can win a victory over a superpower – unless that superpower were willing to use weapons of mass destruction and annihilate the smaller country completely.

President Richard Nixon had spoken bitterly of America as “a pitiful, helpless giant” because of its reluctance to take aggressive military stances in the world that might lead to other Vietnams, a reluctance that came to be known as the “Vietnam syndrome”. In the eyes of the superpower advocates, that syndrome stood for a form of weakness that had to be overcome. The most ringing words of President George Bush Sr., in his immediate response to victory in the first Gulf War in 1991, invoked not heroic warriors (as in Winston Churchill’s classic “Never have so many owed so much to so few”) but a cure: “By God, we’ve kicked the Vietnam syndrome once and for all!”

Those post-Vietnam policies eventually brought about the invasion of Iraq in April 2003. Rather than accept the truth of superpower limitation that lay beneath the “Vietnam syndrome”, such global planners embraced an illusory claim of superpower omnipotence.

Superpower Omnipotence and Vulnerability

It is almost un-American to be vulnerable. Americans pride themselves on being able to stand up to anything and solve all problems. The national self-image involves an ability to call forth reservoirs of strength when needed and a sense of protected existence peculiar to America in an otherwise precarious world. The geographical glorious aloneness thanks to what has been called “free security” of the two great oceans which separate the United States from dangerous upheavals in Europe and Asia. While George Washington was not the isolationist he is sometimes represented to be, he insisted in his celebrated Farewell Address of 1796, “It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances, with any portion of the foreign world”. That image has been embraced, by politicians ever since (He warned against permanent alliances, not alliances in general)

Ironically, superpower syndrome projects the problem of American vulnerability onto the world stage. A superpower is perceived as possessing more than natural power. For a nation to enter into the superpower syndrome is to lay claim to omnipotence, to power that is unlimited, which is ultimately power over death. At the heart of the superpower syndrome then, is the need to eliminate a vulnerability that, as the antithesis of omnipotence, contains the basic contradiction of the syndrome. For vulnerability can never be eliminated, either by a nation or an individual. In seeking its elimination, the superpower finds itself on a psychological treadmill. The idea of vulnerability is intolerable for the superpower and the only solution is to maintain an illusion of invulnerability. Therefore, the superpower runs into the danger of taking increasingly draconian actions to sustain that illusion (read: Gulf War) – And to do otherwise would be to surrender the cherished status of the superpower (More like caught in a catch-22 situation)

This is the core message that I received from the book Superpower Syndrome. It is an insightful work of research and I strongly recommend you to read it.

Thanks for reading.