Economics is a varied subject. There are many perspectives through which a specific viewpoint can be based on. Sadly, the policies effecting the macroeconomics require a gestation period running into decades and therefore the immediate gratification is annulled. The execution of these approved policies need surgeon like precision, which is a challenge. The pitfalls are thus laid on the road of execution and being the foremost reason for the failure of good policies, which are capable of affecting change. Economics is the single most important tool in alleviating global poverty but despite the noble intentions and attempts of great economists, the divisive chasm between the rich and poor continues to grow while the global revenue keeps rising over time, giving a false interlude of a shining tomorrow. In simple terms, the rich are getting richer while the poor are becoming poorer.

The author, Joseph Stiglitz, lays down his perspective of “Globalization” which was considered a great economic policy introduced by the developed countries and adopted by the developing countries (rather forced by the developed countries upon the developing countries, as argued by the author) with a motive to provision every resource available worldwide to the developing countries thus enabling them to grow and diminish poverty. Joseph Stiglitz is the winner of the Nobel Prize for Economics 2001. In this book, Stiglitz narrates his first-hand experience at the World Bank and the policies that ensued with no attempt to conceal his critical views on the subject and the institutions involved.

Preamble

In 1993, Stiglitz left academia to serve on the Council of Economic Advisers under President Bill Clinton. It was his first major foray into policy making, and more to the point, politics. Stiglitz then moved to the World Bank and served as chief economist for three years beginning 1997. It was a fascinating time, as per the author, since Russia began its transition from communism and the financial crisis that began in East Asia in 1997. Stiglitz, dwells on the devastating effect that globalization had on developing countries and especially the poor in those countries.

The author believes that globalization – the removal of barriers to free trade and the closer integration of national economies – can be a force for good and that it has the potential to enrich everyone in the world, particularly the poor. But, if that sentiment is true, the way globalization has been managed, including the international trade agreements that have played such a large role in removing those barriers and the policies that have been imposed on developing countries in the process of globalization, need to be radically rethought. At the World Bank, decisions are often made because of ideology and politics. As a result many wrong-headed actions were taken, the ones that did not solve the problem at hand but that fit with the interests or beliefs of the people in power.

The French intellectual Pierre Bourdieu had written about the need for politicians to behave more like scholars and to engage in scientific debate, based on hard evidence. Regrettably, the opposite happens too often, when academics involved in making policy recommendations become politicized and start to bend the evidence to fir the ideas of those in charge.

Genesis of IMF and World Bank

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank both originated after the World War II as a result of the UN Monetary and Financial Conference at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in July 1944. It was a concerted effort to finance the rebuilding of Europe after the devastation of World War II and to save the world from future economic depression. The proper name of the World Bank – The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development – reflects its original mission, the last part “Development”, was added almost as an afterthought. At the time most of the developing countries were colonies and what meagre economic development efforts could or would be undertaken were considered the responsibility of their European masters.

The more difficult task of ensuring global economic stability was assigned to the IMF. Those who convened at Bretton Woods had the global depression of the 1930s very much on their minds. The Great Depression enveloped the whole world and led to unprecedented increases in unemployment. A quarter of the American workforce was unemployed during a worst point during the 1930s.

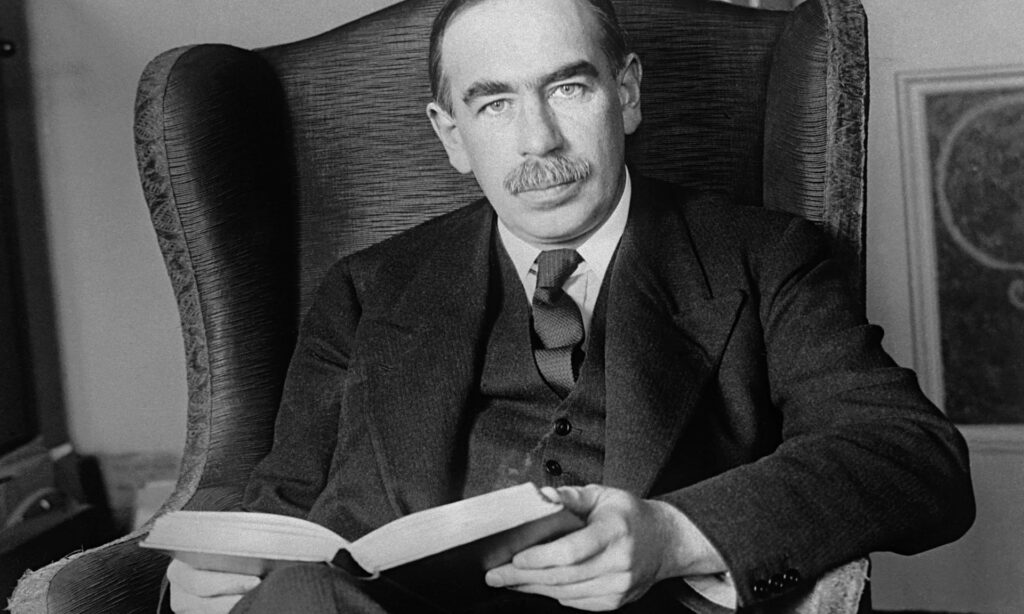

The British economist John Maynard Keynes, who would later be a key participant at the Bretton Woods, put forward a simple explanation, and a corresponding simple set of prescriptions: lack of sufficient aggregate demand explained economic downturn therefore government policies needed to stimulate aggregate demand. Governments could rely on fiscal policies, either by increasing expenditures or cutting taxes, this was if the monetary policy became ineffective. While the models underlying Keynes’s analysis have subsequently been criticized and refined, bringing deeper understanding of why market forces do not work quickly to adjust the economy to full employment, the basic lessons remain valid.

The IMF was charged with preventing another global depression. It would do this by putting international pressure on countries that were not doing their fair share to maintain global aggregate demand. The IMF also provided with loans to the countries to stimulate aggregate demand if the countries found it difficult to attain with their own resources. The IMF is a public institution, established with the money provided by taxpayers around the world. This is important to remember because IMF does not report directly to the citizens who finance it or those whose lives it effects. Rather, it reports to the ministries of finance and the central banks of the governments of the world. The major developed countries run the show, with only one country, the United States, having effective veto. (In a sense, it is similar to the United Nations, where the historical anachronism determines who holds the veto – the victorious powers of the World War II – but at least there the veto power is shared among five countries).

Over the years since its inception, the IMF has changed markedly. Founded on the belief that markets often worked badly, it now champions market supremacy with ideological fervour. Founded on the belief that there is a need for international pressure on countries to have more expansionary economic policies – such as increasing expenditures, reducing taxes, or lowering interest rates to stimulate economy – today, as per Stiglitz, IMF typically provided funds only if countries engage in policies like cutting deficits, raising taxes, or raising interest rates that lead to contraction of the economy. Keynes would have been livid at this metamorphosis of IMF.

Institutionalized Change of Guard

The most dramatic change in the IMF and World Bank occurred in the 1980s, the era when Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher preached free market ideology in the United States and United Kingdom respectively (Thomas Friedman’s view on Globalization – The Lexus and the Olive Tree). The IMF and World Bank became the new missionary institutions, through which these ideas were pushed on the reluctant poor countries that often badly needed their loans and grants.

McNamara had been appointed the president of the World Bank in 1968. Touched by the poverty he saw throughout the third world, he along with his confidant and adviser Hollis Chenery, distinguished development economist, professor at Harvard, assembled a first-class group of economists from around the world to work with them. But with the changing of the guard came a new president in 1981, Willian Clausen, and a new chief economist, Ann Krueger, an International trade specialist, best known for her work on how special interests use tariffs and other protectionist measures to increase their incomes at the expense of others. While Chenery and his team had focussed on how markets failed in developing countries and what governments could do to improve markets and reduce poverty, Krueger saw governments as the problem. Free markets became the solution to the problem of developing countries. In the new ideological fervour, many of the first-rate economists that Chenery had assembled left.

In the 1980s, the Bank went beyond just lending for projects (like road and dams) to providing broad-based support, in the form of structural adjustment loans, but it did this only when the IMF gave its approval – and with that approval came IMF imposed conditions on the country. The IMF was supposed to focus on crisis, but developing countries were always in need of help, so the IMF became a permanent part of life in most of the developing world.

Controversial Globalization?

Opening to International trade has helped many countries grow quickly than they would have otherwise have done. International trade helps economic development when a country’s exports drive its economic growth. Globalization has reduced the sense of isolation felt in much of the developing world and has given many people in the developing countries access to knowledge well beyond the reach of even the wealthiest in any country a century ago. The anti-globalization protests themselves are a result of this connectedness.

Those who vilify globalization too often overlook its benefits. But the proponents of globalization have been, if anything, even more unbalanced. To them, globalization (which typically is associated with accepting triumphant capitalism, American style) is progress, developing countries must accept it, if they are to grow and to fight poverty effectively. But to many in the developing world, globalization has not brought the promised economic benefits.

The critics of globalization accuse western countries of hypocrisy and the critics are right. The Western countries pushed poor countries to eliminate trade barriers, but kept up their own barriers, preventing developing countries from exporting their agricultural products and so depriving them of desperately needed export income. Stiglitz adds, the United States was, of course, one of the prime culprits, and this was an issue about which most protestors felt intensely.

The West had driven globalization agenda, ensuring it garners a disproportionate share of the benefits, at the expense of the developing world. It was that the more advanced industrial countries declined to open up their markets to the goods of the developing countries while insisting that those countries open up their markets to the goods of the wealthier countries. The result was that some of the poorest countries in the world were actually made worse off.

Joseph Stiglitz brings the opaque nature of workings of the global institutions with determined transparency and hopes his book will open a debate that should occur in the more open atmosphere of universities and not just behind the closed doors of the governments and the international organisations.

I would urge you to read one of my other post on globalization based on the book “The Lexus and the Olive Tree by Thomas Friedman“, which gives another glaring perspective on the same subject.

This is the core message that I received from the book Globalization and Its Discontents. It is an amazing book with real life experiences and I strongly recommend you to read it.

Thanks for reading.